Suntory Time

“The Japanese language can express anything it needs to, but Japanese social norms often require people to express themselves indirectly or incompletely.”1

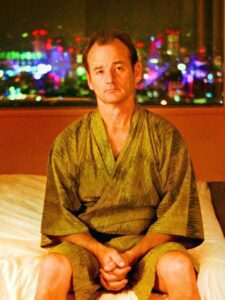

Who does not remember Bill Murray’s estrangement, as he tried to understand the director’s directions on the set of the Suntory Whiskey commercial, in Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation?

Who, as a non-Japanese, has ever thought of being lost in the maze of a language and culture as fascinating as, at first glance, incomprehensible? After all, they have four graphic systems (hiragana, katakana, romaji, and kanji, with the latter comprising thousands of characters of which just over two thousand are taught in schools), which can be easily combined to form intelligible written sentences. The spoken language has no points of contact with ours and even the words of foreign origin, which are footprints in the Japanese vocabulary, are pronounced differently. The grammar is different from ours (the verb is placed at the end of the sentence and reading a literal translation seems to hear Master Yoda speak. No offense intended, I’m a Star Wars fan!). Not to mention the myth of the “vagueness” of the Japanese language.

“No, japanese is not the languge of the infinite. Japanese is not even vague. The people of Sony and Nissan and Toyota did non get where they are today by wafting incense back and forth. The Japanese speak and write to each other like as other literate people do.”2

So misunderstandings are around the corner, especially when dealing with a language as “different” as Japanese can be. And the temptation to label it as “unknowable” and “mysterious” or even “esoteric” is always powerful and also very comfortable. One thing we need to remember is that the Japanese language and culture reveal themselves when they are contextualized. Nothing in Japan exists out of context, “Everything in its place and every place for everything” (I’ll discuss this in more detail in an upcoming newsletter. Stay tuned!).

In the practice of martial arts and Iaido in particular, we inevitably and continually come across Japanese words and expressions that we often struggle to really understand. Let’s take for example the names of kata (forms). Wanting to translate them often makes no sense to us and, at best, they may seem elusive or too evocative. Only with the practice of the form do names acquire a precise meaning. To give you an idea take the name of a kumidachi kata of the Iaido that I practice: nami-gaeshi, which means “wave that returns”. Poetic right? Too bad that the name itself does not mean anything and even in practice, if you do not pay attention, you do not understand much of why they have entrusted it with that name.

So we have to pay attention. We must contextualize.

But why do we have to go to the trouble of understanding these things and not just perform kata and kumidachi as we have been taught? First of all in order not to limit ourselves to sterile practice. And then, because, in the twenty-first century, we must make an effort of further understanding, both for ourselves and for others (our students or less experienced classmates), to evolve in practice and to make it evolve. So what should we do? Taking an intensive Japanese course? It is not necessary, although studying the language is extremely interesting and challenging. We have to pay attention, we have to use Zanshin.

Zanshin (残心), in the context of martial arts, is a state of awareness, of relaxed alertness. A literal translation of zanshin is “remaining mind”. Is a mental aspect maintained before, during, and after action. This is an aspect to always remember: attention must be applied at all times and must be relaxed attention. This applies not only during practice in the dojo but in every aspect of our life. Applying zanshin makes us always aware of our actions. With training, we should succeed to be in zanshin when we perform our daily activities, both at home and in the workplace. Through zanshin we can “read” people or situations. Zanshin is a tool that must be trained day after day and that allows us, for example, to stop the train of thoughts that sometimes invade our minds. It is the means that makes us live in the here and now and at the same time keeps us in the flow. Zanshin is therefore a powerful and essential tool for good practice and for living a good life.

- “Making Sense of Japanese. What the Text Don’t Tell You.” – Jay Rubin (Reprint Edition 2013).

- op.cit.