“There are more things in Heaven and Earth…”1

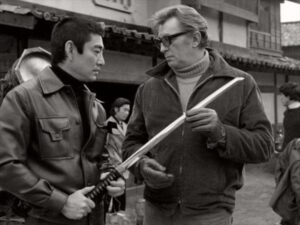

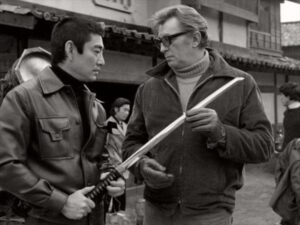

I fell in love with Japan and the Japanese sword as a child, watching a movie on television, Sydney Pollack’s “The Yakuza”2 with Takakura Ken and Robert Mitchum.

The film had all the ingredients to fascinate: it was about honor, love, duty, betrayal, yakuza, there was a lot of action, two protagonists with whom it was easy to empathize, and, one of the first and rare times where Japan and Japanese weren’t treated in caricature roles. And, above all, duels and killings perpetrated with katana blows. For me, a child of the ’70s, it was also the first contact with Japan, with Tokyo, and with all that “exotic” imagery (today it would be impossible for a child to watch alone a movie like “The Yakuza”, but that was another era. Neither better, nor worse, just different.) The anime and manga would arrive shortly thereafter, increasing interest in that “strange Country” more and more, not to mention another film like “Blade Runner” which in a few years would colonize our collective imagination in a way so pervasive.

It would be many years before I picked up a Japanese sword, or rather an iaitō (居合刀), the training sword we use in our art practice. Years of travel, even in Japan, and more or less constant practice of Judo and Aikido. Then, one evening, during training, my Sensei made us give a lesson in Iaido, preparatory to what we were studying. I remember when I picked up the sword and clumsily tried to do what we were told to do, I thought I had found what I had long been looking for in martial arts. Since then I stopped practicing other disciplines and devoted myself to Iaido. Many years have passed since then and the practice of the sword has accompanied me constantly, helping me to overcome complicated moments and making me grow as a person.

The roots of Iaido go back to 16th century Japan, a period of great transformations characterized by the end of the Warring States period, or the Sengoku period, and the beginning of the Tokugawa Shogunate. In this time and in the two and a half centuries to follow the figure of the bushi, more commonly known as samurai, changed drastically. In an era like Tokugawa, characterized by forced pacification, even the men of arms had to radically change their position, not only formally but also in practice. It was in this period that a search for both the psychological and existential meaning of these warless warriors developed and their relationship with what was considered the extension and concretization of their spirit, namely the sword.

The modern Iaido arises from these reflections as well as some misunderstandings concerning it. Often the Iaido is described as a sort of meditation performed with the sword, an inner search that would have the aim of cutting the ego in two with the razor-sharp blade of the katana. The juxtaposition of this martial art with Zen philosophy (certainly real and with practical implications for the ancient bushi) and with a sort of indefinite metaphysics, make us forget not only the original purposes of this art, confining it to the realm of mere intellectual speculation and of a kind of artificial spirituality. It prevents us from doing serious reflection and above all also from developing a series of skills that can allow us to use the sword, not as a weapon, but as a means to find solutions to the problems that afflict us.

One of the most accredited translations of Iaido is to “live in union with the way”. But what is this ‘AI (合)’ union, harmony? Usually, when we think of harmony we are reminded of a world at peace, where agreement reigns supreme (agreement and harmony can be used interchangeably).

The definition of the Cambridge Dictionary is as follows:

a pleasant musical sound made by different notes being played or sung at the same time;

a situation in which people are peaceful and agree with each other, or when things seem right or suitable together;

Perhaps we must consider that the concept of harmony for the Japanese is different. For them, it is not so much a question of creating or re-creating a world of peace in the sense that we understand it (a world without problems and conflicts, which is a very new age thing) but rather of restoring an established order that has been upset by some element out of control, it does not matter if it was internal or external to the society. In ancient and, in some ways, even in modern Japanese society, peace was only possible if all the elements were in their place. So, in this context, living in harmony can be understood as “doing the right thing at the right time”. And, by right thing, we mean that action that restores the established order. If we see things from this point of view, the meaning of AI, harmony, takes on a different meaning, more subtle and more difficult because it forces us to think about our place in the world (especially in this apparently meaningless world). Before going on an ego hunt perhaps it would be better to try to answer this question which is not only existential and pertains solely to the field of ideas but has serious consequences in our daily life.

- The well-known complete sentence is “There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” “Hamlet” Act 1 Scene 5, William Shakespeare (Around 1600)

- The story of the making of this film deserves another post.