Nobody’s Perfect (Nor You or I)

Since the time of Socrates, it has been passed down to us that questions are more important than answers. The Socratic Method has been and continues to be one of the cornerstones of Western philosophy. Our constant questioning forces us to find solutions and answers to both practical and, above all, existential queries. Besides the importance of asking ourselves questions, especially the latter’s quality, it should be emphasized. But we “normal” human beings, above all, want answers and certainties that give meaning to our lives, which is why we embrace beliefs and philosophies, more or less critically, and become part of churches, institutions, clubs, and dojos. We want rules, perhaps to rebel against them, and someone who can tell us what to do and maybe what to think.

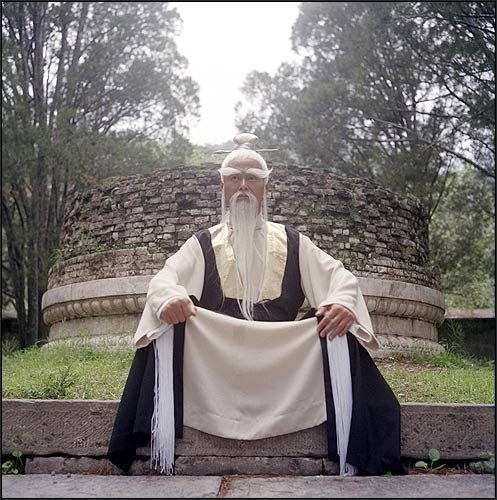

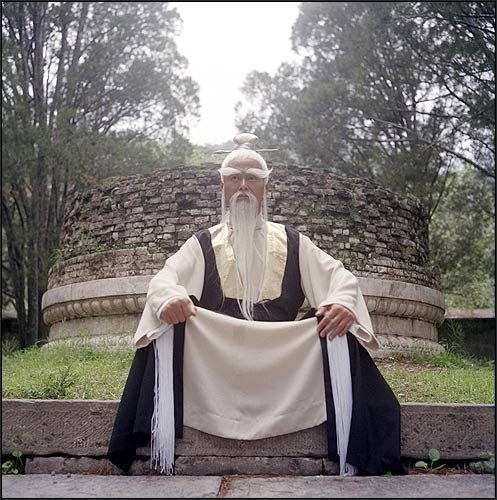

A certain idea of a “master” has been instilled in the field of martial arts. This type of sensei must be a sage who has acquired esoteric knowledge, must possess absolute answers, and know secret techniques that he has learned from ancient masters in dark and mysterious dojos in unknown corners of Japan (or China, Thailand, Philippines, Korea depending on which school or lineage it claims to belong to). He must be at the same time ruthless in applying discipline and teaching techniques, and at the same time be as wise as a Confucian, willing to advise and administer pills of wisdom in the form of acute and incomprehensible aphorisms. Indeed, the more incomprehensible the better. And most importantly, it must be perfect. Unfortunately, this idea has become so ingrained that some teachers believe in it and propose and sell themselves in this way, knowing that there are crowds of students ready to listen to them. Instead, the reality is different.

As mentioned earlier, the word sensei means “the one who came first”. So the teacher is that person who preceded us in the same path that we are also taking, who has stumbled, made mistakes, and learned. And he has reached such a level that he can pass on his knowledge and experiences to those who are moving on the same path, as others have done before him, and others will do it after. That’s all. A sensei is not a superhuman being with superpowers, or arcane knowledge, or the keeper of ancient techniques handed down from father to son since the dawn of time. He is a normal person, with attached strengths and weaknesses, with a mortgage or rent to pay, a family, shopping to do, and so on. But this normality, which belongs to us all, is sometimes difficult to accept. We, from the sensei, expect perfection and do not forgive him in the least that he can put a foot in the wrong. We project on him our expectations and our illusions, which are punctually broken, bringing us back to the reality of life.

“The Son of Man came eating and drinking, and they say, ‘Here is a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners’.” Matthew 11:19

Nobody is immune from criticism, especially those who decide to get involved and take responsibility for passing on their knowledge. Fortunately, many teachers do this without taking themselves too seriously and with a hint of recklessness. But accepting this reality is perhaps one of the most difficult tests for students, especially if they are full of illusions and false expectations. Respecting the person, respecting their role as teachers, knowledge, and experience, without putting them on a pedestal, accepting their fallibility, without idolizing and incensing them, is the most difficult path but the only one that brings lasting results. This is the most important lesson we can learn in the dojo: respect ourselves, respect others, and become adults, as well as make a clean sweep of all the fake “masters” who infect our world.

This does not mean, as students that we have to settle or lower our expectations, and as teachers, this cannot and should not be an excuse to be superficial or to rest on our laurels. Instead, this awareness must be a stimulus to constantly improve ourselves, to put kaizen (改善) into practice in our art, a continuous and constant improvement.